Bible | Movies | Books | People | Hot Topics | Holidays | Humor | Gallery | Sanctuary | Sermons | Prayer | Quizzes | Communities | God | FAQ | Links

|

Sponsored Link |

Not About Me -- An Epiphany

Meditation by Kenneth Arnold

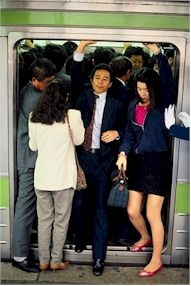

One morning on Forty-Second Street in Manhattan, I see a woman in line to board a bus punch the woman behind her. Her move is quick and practiced. This is not the first person she has slugged. She shouts, "You stop pushing me!" A group of tourists pauses to take pictures, delighted to see New York in action. Others in the bus line step away. The one who was attacked, smaller and older, seems stunned by what has happened. But when her assailant turns her back, she begins pounding her shoulders with glancing and ineffectual blows of rage. Every now and then I am overcome by the number of people on the streets and highways. In New York City the crowds can be oppressive. In the suburbs the volume of cars is numbing. Where is everybody going? Who are all of these people? They pour through the streets endlessly. On the subway, I try to look at faces. Mostly, people are turned in on themselves. They get nervous if I look too long. They do not want to be singled out. But they struggle for position, like the two women boarding the bus. In New York intersections, pedestrians stand in the crosswalks glaring at drivers that try to run the lights. The drivers lean on their horns. Road rage is something we all have seen or felt. It seems to be more common than ever, or just more visible. And yet, somehow, most of us get through the day without being injured or without injuring each other. That seems to me remarkable, that more of us are not killed in the thoroughfares. Lately, when someone pushes by me to take the last subway seat or jumps to the front of the line at the coffee shop, I have been saying, "Please, I want you to be first." The response is usually a murderous stare. Please, I want you to be first. The attitude is a hard one to grasp. (I do it out of anger as a rule and therefore it cannot be counted to me as righteousness.) John the Baptist understood the implications of stepping aside for someone else. He is probably as pure a servant minister as any figure in the New Testament. Suddenly, in the crowds along the Jordan River, he sees Jesus and knows. Out of the chaos comes this still point of light and he sees it. I imagine that the scene freezes for John. Everyone but Jesus stops moving. Imagine being so tuned to creation that even as you are working, even as you are absorbed in your own life, as John was, you sense the arrival of God. A door opens and there, in the light: look! It is what the prophet does, shows us the reality. Prophets are not just the ones who shout, although John apparently was a shouter: the voice of one crying in the wilderness. He is the last of the prophets of Israel, standing in the Jordan at the door to the Promised Land, telling all who will listen, "you are children of the snake." They flock to his abuse, even the ruling classes who should know better. What do they think he is going to say? Jesus later asks the same question. What do you go to the prophet to hear? What do you want to know? The kingdom of heaven crashes like thunder into a cloudless day. We are drawn, as to a wreck by the side of the road. The crowd parts like the waters of the Red Sea. John points. Heads turn. This is a moment when sacred time enters human space. Does anyone else see anything, or is it only John, only the one pointing? John says that this is the one greater than he, the one whose sandals he is unworthy to fasten, the one he has been talking about. The genuine prophet always points beyond the self. John's work is finished--he is finished--the moment this one steps out of the crowd and asks to be washed. John replies, "No. It's the other way around. You wash me. I am not worthy." He was mistaken. When we wash someone else, we give them honor. We acknowledge the holiness of their flesh, even as John recognized in Jesus holy flesh. When our children are young, we wash them. It is often a time of laughter, splashing in the bath. When our parents grow old, sometimes we wash them too, when they are too sick or feeble to care for themselves. This is another kind of reverence, caring for those who brought us into the world, honoring their flesh. A few years ago, when my father was having seizures, I spent some time with my mother taking care of him. Together we would wash him. He is a man who hates to give up control, but he put up with our soaping his body, making a joke of it. "Vi," he said to my mother, "you wash the top part as far down as possible. Ken, you wash up as far as possible. "And," he grinned, "I'll wash possible." I remember the surprise of the smoothness of his skin. It is a moment, this washing of one another, in which we must decrease while the other, the one we wash, increases. Jesus teaches the lesson explicitly on Maundy Thursday, when he insists on washing the disciples' feet. "See what I your Lord have done for you. I have given you an example." The crowds on the highway, the throngs in the subway, are all those Jesus invites us to wash. Among them he is also walking. The crowd washes over us. People push us aside on their way somewhere else. The moment can be terrifying when we are engulfed by strangers. Stuck in traffic, we have nowhere to go. The subway doors close us in with people filled with resentment. Always around us are hundreds of thousands of them, each the hidden presence of God. When all I am thinking about is my own journey home, I will not see the one who is among them. But it is a fearsome thing to look too closely, for when God emerges in the crowd, time stops, as it does for John. After that I must decrease. Salvation is like that. It's not about me.

Image

of the Tokyo subway on this page is from the Corel Corp. and is protected by the

copyright laws of the U.S., Canada and elsewhere. Used under license.

Please take a moment to let us know you

were here!

If you want to talk with someone in person, please feel free to call 917-439-2305

The Rev. Charles P. Henderson is a Presbyterian minister and is the author of God and Science (John Knox Press, 1986). Charles also tracks the boundry between the virtual and the real at his blog: Next World Design, focusing on the mediation of art, science and spirituality in the metaverse. For more information about Charles Henderson. |

Sponsored Link

|