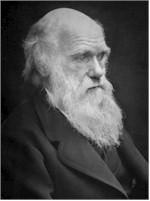

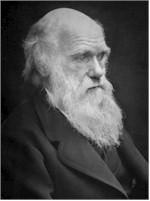

| CHARLES DARWIN

The Origins of Doubt

and the Rebirth of Praise Chapter

3 of God and Science

by Charles

P. Henderson, Jr.  One

cannot begin to fathom the dilemma of western culture without reflecting upon

Charles

Darwin and The

Origin of Species. Obviously, Darwin's theories about the evolution of

life on this planet stand at the very center of the controversy between science

and religion. We are reminded of this by the increasing efforts of creationists

to gain equal time for the Bible in the public schools of America, but these rearguard

efforts to turn back the pages of history and re-enact the Scopes

trial are of far less significance than the continuing cold war between the

world's leading scientists and theologians. For this is a controversy being conducted

not in the rural countryside of Arkansas and Nebraska but in the leading universities

and at the most advanced frontiers of human thought. One

cannot begin to fathom the dilemma of western culture without reflecting upon

Charles

Darwin and The

Origin of Species. Obviously, Darwin's theories about the evolution of

life on this planet stand at the very center of the controversy between science

and religion. We are reminded of this by the increasing efforts of creationists

to gain equal time for the Bible in the public schools of America, but these rearguard

efforts to turn back the pages of history and re-enact the Scopes

trial are of far less significance than the continuing cold war between the

world's leading scientists and theologians. For this is a controversy being conducted

not in the rural countryside of Arkansas and Nebraska but in the leading universities

and at the most advanced frontiers of human thought.

To be sure, the contradictions

between evolution and the Bible have been addressed again and again. In fact,

the critical issues were successfully resolved long before Darwin published his

views on natural selection in 1859. What has not been repaired is the breach that

opened up between science and religion generally in the period following the publication

of TheOrigin.

Darwin realized that he had opened up the most serious problems at the

interface of science and religion, but in the end he could not resolve them even

to his own satisfaction. He ended his career in a state of total confusion about

the one problem which his great book purports to solve; namely, how to explain

the origin and evolution of life in scientific terms without an appeal to religion.

As he confided in a letter to one of his closest colleagues, "I am in an

utterly hopeless muddle."'(1) Darwin's

failure to resolve the problem of faith both personally and as a professional

scientist has had a lasting effect upon scientific endeavor since the 1850s. When

Darwin set out on his

epic voyage aboard the H. M. S. Beagle in 1831, he had no intention of rocking

the world with controversy. At the beginning of his journey he was not a seasoned

scientist well-equipped to address the fundamental issues of his time. He was

a fresh graduate of Cambridge with a degree in theology. His personal agenda was

to complete the requirements for ordination in the Church

of England and secure a quiet, country parish where he could practice the

ministry while at the same time pursue his favorite hobbies: hunting, fishing,

and collecting rare specimens of rocks or beetles. His appointment as a "naturalist"

on what was conceived as a routine scientific expedition to the southern coast

of Tierra del Fuego would

not yet have qualified Darwin as a professional scientist. The British Admiralty

was not prepared to pay his salary; the government would only provide for his

expenses and accommodations aboard the unwieldy and unseaworthy Beagle; but the

chance to circumnavigate the globe and explore the coast of South America appealed

to his sense of adventure. The Beagle sailed on December 27, 1831, a date

which Darwin later marked as the beginning of his "second life."(2)

The notations in his diary and his letters home mark out the successive steps

in the transformation from enthusiastic amateur to serious and dedicated man of

science. To his father he wrote, "I think if I can so soon judge, I shall

be able to do some original work in natural history. I find there is so little

known about many of the tropical animals."(3)

At the beginning of the voyage his primary enthusiasm was

for hunting, but after two years at sea he had given up his gun and had thrown

himself entirely into the task of collecting specimens of rocks, plant life, and

animals. Again he wrote home, "There is nothing like geology; the pleasure

of the first day's partridge shooting or first day's hunting cannot be compared

to finding a fine group of fossil bones, which tell their story of former times

with almost a living tongue."(4) Already Darwin

had exhibited a penchant for metaphor which, as we shall see, was central to his

own thinking and characteristic of that whole mode of thought which today goes

by the name of Darwinism.

If

popular conceptions of the scientific endeavor call to mind technicians dressed

in white robes in a laboratory somewhere, Darwin's journey aboard the Beagle gives

us quite an alternative view. As the Beagle traced its course around the continent

of South America, Darwin explored areas as diverse as the barren Falkland Islands,

the tropical rain forest, the Rio Negro, and the volcanic mountains of Chile.

On February 20, 1835, Darwin had one of those experiences that change the character

of one's whole life work. While exploring the mountains near Valparaiso,

his imagination was drawn to the solid masses of granite rising up out of the

forests "as if they had been coeval with the very beginning of the world."(5)

The granite fascinated him because it seemed to be the most basic and fundamental

building block in the earth's solid crust. Penetrating to this basic, geological

bedrock seemed to bring one close to the "classic ground" of creation.(6)

However, as he lay peacefully in a forest near Valdivia

speculating about such impressions of nature, he felt the shock waves of a major

earthquake. In the forest the drama of the earthquake was shocking enough, but

when he returned to the port at Talcuhano he was horrified to find that every

dwelling place had been demolished. The earth itself had been rent by deep crevasses,

and the granite rock formations, which formerly appeared so solid and unshakable,

had been shattered into fragments. "An earthquake like this at once destroys

the oldest associations; the world, the very emblem of all that is solid, moves

beneath our feet like a crust over a fluid; one second of time conveys to the

mind a strange idea of insecurity, which hours of reflection would never create."(7)

As Darwin's awareness of nature broadened and deepened, so the solid crust

of conventional scientific wisdom began to disintegrate. That all things are in

a state of change and flux may have been the most important lesson which Darwin

brought home from his long voyage. Darwin's notebooks give ample evidence of a

mind itself going through a process of transformation. His imagination raced from

one subject to the next. He did not focus upon any single issue of science; rather

his thoughts ran free across the fields of geology, biology, paleontology, and

anthropology. Curiously, in proportion as he became more deeply fascinated by

science, Darwin became less interested in religion. He never seemed to experience

a particular crisis of faith, but gradually and steadily his faith simply disappeared.

He described the change much later in the pages of his Autobiography;

| I

had gradually come, by this time, to see that the Old Testament from its manifestly

false history of the world, with the Tower of Babel, the rainbow as a sign, etc.,

etc., and from its attributing to God the feelings of a revengeful tyrant, was

no more to be trusted than the sacred books of the Hindoos, or the beliefs of

any barbarian.... I gradually came to disbelieve in Christianity as a divine revelation....

Thus disbelief crept over me at a very slow rate, but was at last complete.(8)

| Such passages from Darwin, and there are

many others of a similar nature, seem to offer to both defenders of faith and

to devotees of secular science an obvious lesson. The moral drawn by both camps

is that Darwin's life and work demonstrate the incompatibility of religion and

science. Believers should avoid science because scientific inquiry inevitably

conflicts with and possibly destroys religious faith; and, likewise, scientists

should avoid religion because it has no more to do with the pursuit of truth than

the "beliefs of any barbarian." There seems to be a perfect syllogism

here: true religion is undermined by science, and a true science is corrupted

by religion; therefore, the two are locked in unceasing conflict. As tempting

in its simplicity as this conclusion appears to be, and though this is precisely

the lesson drawn out of Darwin by serious scientists and people of faith today,

it simply cannot be sustained in the face of a deeper inquiry into his life and

work. To be sure, one must push to a level of analysis beyond that required

in the acknowledgment that certain biblical stories, like the narrative of the

tower of Babel, present a "manifestly false history of the world!" If

belief in God stands or falls on the historical accuracy of such stories, then

the world's major religions would not have survived to Darwin's time. The question

as to the truth or falsehood of religion, and its relevance to science, hinges

on more basic issues than this, and Charles Darwin, drawing on his Cambridge theological

education, was capable of wrestling with the issues at the deepest level. When

Darwin reflected upon the vast diversity of life as he saw it in the natural world

and when he tried to understand how the various species came to be distributed

in all their variety across the face of Europe and America, he quickly saw that

the central issue was not so much a specific conflict between the affirmations

of the Bible and the facts of natural history. Many leading scientists and theologians

alike had recognized that the Bible could not be taken literally as providing

an accurate or complete history of the natural world. The theory of evolution

had been proposed long

before Darwin's birth. In fact, his grandfather Erasmus

Darwin, had been one of evolution's leading exponents. Evolution had been

widely debated in theological as well as in scientific circles, but until Darwin

no one had demonstrated that evolution shed any more light upon the mysteries

of life's origins than the reigning theory of that era. In the opening

decades of the nineteenth century the most widely accepted explanation for the

diversity and distribution of life was the theory of special creation. According

to this popular notion, all creatures great and small were the direct product

of a special act of God. Whatever the sequence of timing, the place of origin,

the pattern of migration, the growth or decline of populations, the crucial point

was that each species was specifically created by God and uniquely adapted by

the Creator for a particular setting in the natural world. A common corollary

of this theory was that the species, as created by God, were immutable. Since

God had designed each creature for a specific purpose at a particular time, any

change in the characteristics of a species would be a perversion in God's plan

of creation. In this view all life had been frozen in about the same form since

creation. It is important to note that the theory of special creation is not exclusively

the product of religion; it is not even rooted in the Bible. It was a conclusion

supported as much by science as by religion. Furthermore, special creation

seemed to explain a great deal of what any good scientist saw in looking out upon

the natural world. What any careful observer finds in nature is a vast array of

animals all wonderfully adapted to their environments. Polar bears have thick

fur capable of retaining body heat under conditions of extreme cold; fish have

gills to draw oxygen from water just as lungs draw oxygen from the air. Likewise,

birds have wings designed with awesome efficiency to carry them in graceful flight.

Such observations, carried out rigorously and systematically, together with a

careful analysis of animal behavior and anatomy, provided the underpinnings for

the life sciences. All this early scientific work proceeded under the banner of

special creation. The theory was both comprehensive and overarching; and it was

thought to lie at the core of both science and religion, holding both together.

The problem was that special creation had become a quick substitute for understanding.

Darwin was the first to show that a systematic appeal to special creation as an

all-encompassing dogma was incompatible with true science (just as, he went on

to suggest, it was incompatible with religion). For, once one affirms that

a specific creature is a work of God, what more is there to learn? Having said

all there is to be said about the ultimate origins of life, what interest remains

to explore the finite questions, the detail that is required for a clearer understanding

of why each creature has come to be or by what means the creator proceeds? Moreover,

the theory of special creation tended to support the impression that each species

was the result of divine fiat. An all-powerful God need not follow any prescribed

laws; a particular species can be created by God completely without reference

to any existing patterns or principles of nature. Were life in fact created in

this way science would he quite literally impossible, for studying one creature

or even one thousand creatures might tell one absolutely nothing about any other

creatures. The secrets of life would be locked forever within the inscrutable

mind of God. Throughout his career Darwin's attacks upon special creation

became continually more unrestrained. In the Origin, he chides those

who affirm this theory:

| Do they really believe that at innumerable periods in the

earth's history certain elemental atoms have been commanded suddenly to flash

into living tissues? Do they believe that at each supposed act of creation one

individual or many were produced? Were all the infinitely numerous kinds of animals

and plants created as eggs or seed, or as full grown?(9)

| Darwin clearly saw that special creation,

taken as a total explanation for the origin of the species, was the fit subject

of satire. Writing much later in The Descent of Man (1871), Darwin was

totally unrestrained. Unless one is content to look at the phenomena of nature

"like a savage," he argued, one "cannot any longer believe that

man is the work of a separate act of creation."(10)

Unfortunately, by the time he reached the degree of certainty required by his

accusation that the proponents of special creation must think like savages, Darwin

appears to have left behind him the major lesson of his own theological education.

Also, in waging his battle against special creation he resorted to strategies

of satire and derision which prevented him from taking his own theology much beyond

where he had abandoned it to take up his adventures aboard the H. M. S. Beagle.

At

Cambridge Darwin had read the work of William

Paley who was the Church of England's most influential theologian. Paley was

required reading at Cambridge and Darwin had to pass examinations on what were

thought to be Paley's most important books, Evidences of Christianity and

Moral and Political Philosophy. As an undergraduate Darwin approved

so much of Paley that he went on to read Natural Theology, a work of

more lasting significance and the one which made the deepest impression on him.

At the core of Paley's theology is a clear and vivid analogy which makes his whole

work seem deceptively simple. Paley's book begins:

| In

crossing a heath, suppose I pitched my foot against a stone, and were

asked how the stone came to be there; I might possibly answer, that, for anything

I knew to the contrary, it had lain there forever: nor would it perhaps be very

easy to show the absurdity of this answer. But suppose I had found a watch upon

the ground, and it should be inquired how the watch happened to be in that place;

I should hardly think of the answer which I had before given, that, for anything

I knew, the watch might have always been there. Yet why should not this answer

serve for the watch as well as the stone?(11)

| The reason, says Paley, is obvious. A simple

examination of the watch leads the mind inexorably forward:

| The inference, we think, is inevitable; that the watch must

have had a maker; that there must have existed, at sometime, and at some place

or other, an artificer or artificers, who formed it for the purpose which we find

it actually to answer; who comprehended its construction, and designed its use.

(12) | So,

too, continues Paley, all the works of nature, indeed, "every organized natural

body" whether plant or animal, simple or complex, likewise leads one inevitably

to the conclusion that it too must have a maker.

| For every indication of contrivance. every manifestation

of design, which existed in the watch, exists in the works of nature; with the

difference, on the side of nature, of being greater and more, and that in degree

which exceeds all computation. I mean, that the contrivances of nature surpass

the contrivances of art, in the complexity, subtilty, and curiosity of the mechanism;

and still more, if possible, do they go beyond them in number and variety.(13)

| Thus, Paley concludes, all the works of nature

point to God in the same way that a simple machine points to its human maker.

In this analogy Paley was repeating a formal argument which had been used many

times before by philosophers and theologians, but he stated it in such a clear

and convincing way that he gained a place in the history of ideas if only because

his presentation was so lucid. Yet there was more to commend Paley's book

than its clarity. Paley argues not only as a theologian but also as a scientist.

His text is generously salted with references to scientific literature of

the period. He displays a familiarity with the latest findings in fields as disparate

as biology and astronomy. Like Darwin, Paley's mind reached across the boundaries

of every scientific discipline to draw the most comprehensive inferences and conclusions.

Writing at the turn of the century, he even dealt in some depth with the latest

theories of evolution as they had been developed a full decade before the birth

of Charles Darwin (1809). Paley rejected evolution for precisely the same reason

Darwin found these earlier theories to be unsatisfactory; that is, they could

provide no real explanation how or why particular life forms emerged or what laws

guided their development. Early theories of evolution could not provide a coherent

explanation for the existence of birds as distinct from mammals, not to mention

the larger challenge of accounting for the origin of the human species. Paley

was justified in rejecting evolution in 1801 on purely scientific grounds; a great

deal of research was needed before evolution could be raised as a comprehensive

theory that would replace the notion of special creation. One further point

needs to be emphasized about Paley. His description of God's creative work in

and through the natural world anticipates and successfully avoids the shortcomings

of special creation, narrowly conceived. Paley argues that God's activity in the

world does not consist in setting aside the laws of nature to impose a supernatural

power and superior intelligence upon the mindless face of the material world.

"When a particular purpose is to be effected, it is not by making a new law,

nor by the suspension of the old ones, nor by making them wind, and bend, and

yield to the occasion; (for nature with great steadiness adheres to and supports

them;)."(14) But it is, according to Paley,

by an activity "corresponding with these laws" that God works to create

the wonders of nature. In fact, for Paley, God has sacrificed omnipotence, allowing

the creative process to proceed according to clearly discernible laws of nature,

and it is in and through the very laws of nature that God has accomplished the

creation of life. "It is this," concludes Paley, "which constitutes

the order and beauty of the universe. God, therefore, has been pleased to prescribe

limits to his own power, and to work his ends within those limits. The general

laws of matter have perhaps the nature of these limits."(15)

In fact, Paley's understanding of creation allows for the maximum element

of continuity, uniformity, and regularity in nature. Far from setting up a wall

against further scientific inquiry, Paley's natural theology represents an invitation

and even a prelude to science, for under the rubric of his natural theology one

may regard the phenomenon of nature with constant reference to the Creator. "The

world thenceforth becomes a temple, and life itself one continued act of adoration."(16)

As indicated earlier, there lies an analogy at the heart of Paley's work,

and for purposes of comparison the analogy can be represented graphically as follows:

| watchmaker |  | creator |

| |  |

| watch |  | creation |

Paley put his analogy forward as a logically coercive

proof for the existence of God, and, while his argument remains popular and appealing

to many people even today, it has been attacked by philosophers of science

and theologians so systematically and with such force that the impression is created

that William Paley is completely pass�. His four-sided analogy has been attacked

from all sides by those who fail to see any justification for comparisons between

a watch and a work of nature, between a watchmaker and God; it has been similarly

asserted that one can learn nothing more about God from the study of creation

than one could learn about a civilization which produced watches if one had no

more evidence than an isolated mechanical device found by accident in a "heath"

somewhere.

Indeed, the whole force of Paley's

argument does rest upon his famous analogy, and he illustrates the first analogy

with a second. Compare, he suggests, the human eye and the telescope. Both evidence

similar principles of design and construction; both are modeled according to the

same laws of optics; the eye differs only in being more versatile and more subtle

in its operations. As the telescope is inconceivable apart from its designers,

so too is the eye. In fact, Paley argues that an examination of the eye is itself

a cure for atheism. Thus Natural Theology consists of one analogy following

after the next, and in the simple observation that this is so Paley's whole work

has been written off as dead. For what is an analogy but an attempt to bring to

light the hidden relationships between two or more dissimilar things? It is a

bridge between two worlds, constructed of mere words. Surely, that is no proof

of God! As a proof, Paley's argument is rightly open to such criticism,

for all analogies fall apart if you push them too far. However, Paley has been

consigned to the footnotes of history far too readily by contemporary scholars.

Today Paley is not only out of fashion, his Natural Theology is out of

print. I believe this is a situation which should be corrected if only for the

clarity which Paley brings to our understanding of Darwin, or, putting it the

other way around, Darwin's misunderstanding and misreading of Paley needs to be

accounted for because it is at precisely this point that Darwin's own theory falls

apart.

Darwin thought that he had not only mastered Paley at

Cambridge but also that he had defeated Paley in the formulation of his own concept

of evolution. Hence he wrote in The Autobiography:

| The old argument of design in nature, as given by Paley,

which formerly seemed to me so conclusive, fails, now that the law of natural

selection has been discovered. We can no longer argue that, for instance, the

beautiful hinge of a bivalve shell must have been made by an intelligent being.

like the hinge of a door by man.(17) |

Most contemporary scholars accept Darwin's words about

Paley at face value. For example, historian Neal C. Gillespie, drives another

nail into the Paley casket in Charles Darwin and The Problem of Creation.

"It has been generally agreed (then and since) that Darwin's doctrine

of natural selection effectively demolished William Paley's classical design argument

for the existence of God."(18) In fact, Gillespie

is one of those secular interpreters of Darwin who goes to great lengths to reinforce

the impression that the lesson to be drawn from Darwin is precisely that science

and religion are completely unrelated and incompatible. "In the final analysis,"

he writes, "Darwin found God's relation to the world inexplicable; and a

positive science, one that shut God out completely, was the only science that

achieved intellectual coherence and moral acceptability."(19)

Gillespie convincingly argues that in order to transcend

the limits of special creation it was easier to "shut God out completely."

When a single theory so dominates the world of thought that further inquiry into

basic questions becomes impossible, then certainly a case can be made for taking

another look at the particular assumptions behind such a theory. However, if special

creation had become such a debilitating dogma then, it certainly is not so now.

In fact, when the best work of an important theologian like Paley can be dismissed

in a phrase, as Gillespie has Darwin dismissing Paley ("Darwin downed Paley"(20)),

then perhaps it is time to look through the wreckage of the old theory to see

whether there are any useful elements that have been wantonly abandoned. In this

case, a comparison of William Paley's natural theology with Darwin's own theory

of natural selection reveals that Darwin did not defeat Paley after all; rather,

he incorporated Paley into his own theory. While denying that he could

see the design that Paley saw in nature and loudly protesting the doctrine of

special creation, he describes natural selection in such a way that the element

of design in nature becomes all the more pronounced. While Darwin's theory is

today put forward as a replacement for Paley, Darwin and Darwinism may be Paley's

most important product. Yet the credits are denied not just to Paley, but more

importantly to God.

If Paley's theology can be reduced

to an analogy, all the more so can natural selection. The step-by-step process

that Darwin went through in putting together his theory is well documented by

friends and foes alike, and there is almost universal agreement as to what constitutes

his basic building blocks. The most concise and at the same time accurate account

of the origin of The Origin is contained in an essay by Stephen

Jay Gould, who may be the leading disciple of Darwin today. Gould teaches

biology at Harvard and his series of articles and books on natural history in

itself constitutes an important milestone in the relationship between science

and religion. More on Gould later, but first to his anatomy of natural selection.

Always alert to the possibility that Charles Darwin is not the most perceptive

interpreter of Darwin, Gould cites a note in what he calls Darwin's "misleading

autobiography":

| In October 1838, that is, fifteen months after I had begun

my systematic inquiry, I happened to read for amusement Malthus on Population,

and being well prepared to appreciate the struggle for existence which everywhere

goes on ... it at once struck me ... I had at last got a theory by which to work.(21)

| Gould draws upon his encyclopedic knowledge

of the literature to demonstrate that Darwin did not stumble blindly upon Malthus.

Rather, Darwin was intentionally rereading Malthus following an excursion into

the distant fields of philosophy and economics. Just prior to his rereading of

Malthus, he read a long review of philosopher Auguste

Comte's Cours de philosophie positive. In this work Comte insists

that any useful theory must be both predictive and, at least potentially, quantitative.

Darwin then read a book on Adam

Smith, the economist whose theory of society focuses upon the actions of the

individual as the key element in a market economy. The work of a philosopher and

an economist lead Darwin next to a statistician, Adolphe

Quetelet, who had applied a statistical analysis to the now famous and controversial

claim of Malthus that the human population grows geometrically and food production

only arithmetically, thus resulting in an inevitable and tragic "struggle

for survival." Summarizing these intellectual wanderings, Gould writes:

| In reading Schweber's detailed account of the moments preceding

Darwin's formulation of natural selection, I was particularly struck by the absence

of deciding influence from his own field of biology. The immediate precipitators

were a social scientist, an economist, and a statistician. If genius has any common

denominator, I would propose breadth of interest and the ability to construct

fruitful analogies between fields. In fact, I believe that the theory of natural

selection should be viewed as an extended analogy--whether conscious or unconscious

on Darwin's part I do not know--to the laissez faire economics of Adam Smith.(22)

| Adam Smith's argument is the still familiar

assertion used by those who favor an unrestrained, free-market economy. In order

to achieve a productive economy providing maximum advantage and opportunity for

all, individuals must pursue their private interests unrestrained by government

or monopolies. Ironically, the maximum public good flows inevitably and naturally

from the maximum pursuit of private profit. The theory of natural selection is

nothing less and not much more than a simple analogy taken from the economics

of Adam Smith and applied to the whole realm of living things. As individuals

in the simple pursuit of their own private interests inadvertently strengthen

the whole economic and social structure, so individual animals in their struggle

for survival inadvertently work toward the betterment of a whole species.

In reading Malthus through the lens provided by Adam Smith, Darwin

transformed Malthus from a prophet of doom into a prophet of evolution's unlimited

promise. In so doing, Darwin drew still another analogy, this one from his own

experience as a pigeon breeder. It is crucial to note that the very term "natural

selection" refers to the activity of the breeding of domestic animals and

is a precise analogy. As the pigeon breeder selects only those individuals showing

the most desirable traits as most suitable for breeding, so nature selects those

individuals best suited for survival, thus resulting in the slow but steady "improvement"

of the whole animal kingdom. Note that Darwin's theory also took the form of a

simple, four-sided analogy which may be depicted accordingly:

| pigeon

breeder |  | natural

selection |  | |  |

| pigeons |  | nature |

Thus Darwin proceeds from an analogy taken from the

economics of Adam Smith to an analogy taken from his own experience as a pigeon

breeder. The comparison with Paley is not limited to their penchant for analogies,

for, when we make a specific comparison between the work of natural selection

as described by Darwin and the work of God as described by Paley, the parallels

are exact. Darwin depicts nature as a "power, acting during long ages and

rigidly scrutinising the whole constitution, structure, and habits of each creature,--favoring

the good and rejecting the bad."(23) Similarly

Darwin writes:

| It may metaphorically be said that natural selection is

daily and hourly scrutinising, throughout the world, the slightest variations;

rejecting those that are bad, preserving and adding up all that are good; silently

and insensibly working, whenever and wherever opportunity offers, at

the improvement of each organic being.(24) |

Darwin dearly states that there is a grand design in

the silent and invisible work of natural selection. "We may look with some

confidence to a secure future of great length. And as natural selection works

solely by and for the good of each being, all corporeal and mental endowments

will tend to progress toward perfection."(25)

We remember that it was William Paley who was accused of being overly optimistic!

In fact, when one summarizes all the things which Darwin has natural selection

doing toward the creation and improvement of life on this planet, one has an exact

duplicate of what Paley and theologians generally attribute to God. Thus if natural

selection does everything that God is supposed to do, don't we simply have God

by another name?

As conceived by Charles Darwin, the

theory of natural selection shuttles back and forth between science and religion

and does the work of both. In this context there is a further likeness between

William Paley and Charles Darwin. Both worked at the interface of science and

theology; they both developed and popularized powerful metaphors of creation.

Both Paley's natural theology and Darwin's natural selection are basically creation

myths much like the Gilgamesh epic or the stories of Genesis. They both give a

clear and coherent account of the origins of human life that make it accessible

to human understanding and invite further study. For the same reasons Paley's

analogies have been rejected as a proof of God, Darwin's could be rejected as

science. Darwin was himself aware of this difficulty, and he commented:

| It has been said that I speak of natural selection as an

active power or deity; but who objects to an author speaking of the attraction

of gravity as ruling the movements of the planets? Everyone knows what is meant

and implied by such metaphorical expressions; and they are almost necessary for

brevity. So again it is difficult to avoid personifying the word Nature; but I

mean by Nature, only the aggregate action and product of many natural laws, and

by laws the sequence of events as ascertained by us. With a little familiarity

such superficial objections will be forgotten.(26)

| Yet we are in the grips of something more

that a "superficial objection." Here Darwin is up against that fundamental

problem of both science and theology; indeed it is the problem of cognition itself.

In every science, including the science of theology, it is necessary to make generous

and liberal use of analogies. In the pursuit of knowledge, analogies are the best

we humans can come up with, for we only have a human way of speaking and a human

way of understanding inhuman, superhuman, or sub-human things, and there is precious

little that is human in this wide universe. We only occupy a tiny niche; we are

the angels dancing on the head of a pin. As we look out upon the world and as

we attempt to understand what is happening in a dimension beyond the immediate

reach of our five senses, we have got to depict what is happening in human terms.

Our analogies, our metaphors, and our anthropomorphic images are all that stand

between ourselves and the external world. Darwin demurred briefly before this

situation but tried to pass it off as a minor problem--"everyone knows what

is meant and implied by such metaphorical expressions"--but, of course, it

is rather the case that no one knows what is meant by such metaphors. If the whys

and wherefores of life on this planet could be included among the things everyone

knows, then both science and theology would be superfluous. Also, look

what happens to natural selection when Darwin tries to get behind the analogy

to a bedrock of fact which everyone can know. Behind his own images which personify

nature Darwin asserts that "I mean by Nature, only the aggregate action and

product of many natural laws, and by laws the sequence of events as ascertained

by us." Hence there actually is no other basis or bedrock of fact behind

his theories after all, except a sequence of events-- as ascertained by us.

Darwin, though, tried to do much more than give an accurate account of the sequence

of events which we call natural history. He tried to give a scientific accounting

of the precise relationship that exists between one event and another. Likewise,

like a theologian, he tried to plumb the meaning of life's basic processes. He

maintained that natural selection, even as it represented an advance in science,

also advanced our understanding of God. As he put it in the concluding sentences

of the Origin:

| To my mind it accords better with what we know of the laws

impressed on matter by the Creator, that the production and extinction of the

past and present inhabitants of the world should have been due to secondary causes....

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally

breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet

has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning

endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved?(27)

| Such positive and even rhapsodic passages

are counterbalanced in Darwin by those comments inspired by the darker side of

nature and natural selection. For, if natural selection works toward the improvement

of every living being, nature moves each species forward with the inexorable force

of extinction and death, eliminating by sudden violence, starvation, or any other

of a thousand natural calamities all those unfit for survival. Darwin tried

to justify the element of waste and wanton destruction in the natural world in

much the same way theologians try to reconcile the existence of evil and suffering

with the existence of an all-powerful and all-loving God. He wrote in Natural

Selection:

| We must regret that sentient beings should be exposed to

so severe a struggle, but we should bear in mind that the survivors are the most

vigorous & healthy & can most enjoy life: the struggle seldom recurs with

full severity during each generation: in many cases it is the eggs, or very young

which perish.(28) | One

might ask, though, how Darwin could take the measure of an animal's joy or fear

for the purposes of comparison. Darwin makes a bold attempt to bring suffering

and death under the protection of evolution's all-embracing arms, but in the last

analysis he meets with little more success than theologians who try to solve the

problem of evil by talking of God's mysterious and inscrutable will. In Darwin's

case the form of his argument is clearly that in nature's case the end justifies

the means: "Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most

exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the

higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life."(29)

Yet Darwin was aware that such "answers" are only partly satisfying

and at times he pondered the possibility that there was no grand design in nature

after all. Perhaps evolution moved forward haphazardly; perhaps even the highest

forms of life, even humanity itself, are the product of blind chance. Shortly

after the publication of The Origin he carried on a long correspondence

with his friend and colleague, Asa

Gray, confessing his own doubts and his sense of confusion about the end and

ultimate directions of evolution.

| I am conscious that I am in an utterly hopeless muddle.

I cannot think that the world, as we see it, is the result of chance; and yet

I cannot look at each separate thing as the result of Design.(30)

I am in thick mud; the orthodox would say in fetid abominable mud. I believe

I am in much the same frame of mind as an old gorilla would be in if set to learn

the first book of Euclid... yet I cannot keep out of the question.(31)

| Darwin kept wavering throughout his lifetime.

At one moment he would express confidence that natural selection represented nothing

less than God's own design impressed upon the face of this whole creation. Evolution

itself then amounted to nothing more than a random sequence of events strung together

by fiat of the human mind. Darwin wandered between these possibilities throughout

his life. He never succeeded in climbing his way out of his theological muddle.

Many disciples of Darwin have no such difficulty.

Stephen Jay Gould, for example, is absolutely clear: God does not superintend

natural selection. In fact, Gould extends himself again and again to say that

evolution follows its own rules and heeds its own counsel; it cannot be the work

of a divine Creator. By way of illustration, Gould argues in The Panda's Thumb:

| Our textbooks like to illustrate evolution with examples of optimal

design--nearly perfect mimicry of a dead leaf by a butterfly or of a poisonous

species by a palatable relative. But ideal design is a lousy argument for evolution,

for it mimics the postulated action of an omnipotent creator. Odd arrangements

and funny solutions are the proof of evolution-paths that a sensible God would

never tread but that a natural process, constrained by history, follows perforce.

No one understood this beter than Darwin.(32)

| Gould quotes Francois Jacob to the effect

that nature is "an excellent tinkerer, not a divine artificer."(33)

What his beguiling essay (and indeed his lifework in natural history) adds up

to is the argument from design turned against itself. Gould tries to turn Paley

upside down. The designs we see in nature resemble those of an amateur inventor,

not an omnipotent Creator; parts originally fitted for one function are adapted

to another; new species are "jury-rigged from a limited set of available

components."(34) What Gould tries here, and

elsewhere in his writing, is the most obvious and familiar maneuver of scientific

atheism. He sets up God as a Perfect Being for the explicit purpose of showing

how such a God could not possibly have created this imperfect world. In so doing

he seems entirely oblivious to the lesson which "no one understood better

than Darwin"; namely, William Paley's simple point that God, limited only

by the laws of nature, must rely on artifice and contrivance. Whereas Paley rummaged

the whole natural world for examples of God's design, Gould searches the same

territory for those awkward, amateurish moves which show nature to be guided by

something less than an omnipotent, omniscient Creator.

Gould writes eloquently, vividly, and graphically of natural selection;

he uses one metaphor after another, but he assiduously avoids religious metaphors.

In fact, he favors images drawn from the age of machines. He calls natural selection

the "primary mechanism" of evolution. In another context, discussing

human evolution, he writes: "We are here for a reason after all, even though

that reason lies in the mechanics of engineering rather than in the volition of

a deity."(35) One wonders why it is more

acceptable to see nature working like a machine. A machine is a human contrivance.

To see evolution working like a machine does not solve the problem many scientists

have seen in religion. If it is misleading to refer to creation as an act of God,

it is doubly misleading to describe it as a machine. In making the transition

from the former metaphor to the latter, one has only complicated matters, resorting

to a more obscure form of anthropomorphic imagery.

The fact is we are locked into a position of having to describe inscrutable phenomena

in terms accessible to human understanding. One can conceal this fact by resorting

to abstractions or oblique images like Gould's, but one cannot thereby climb out

of the muddle which is the human condition. All his disclaimers aside, Gould still

describes natural selection as the creator, sustainer, and superintendent of life;

as in Darwin, so in Gould, natural selection intervenes in nature to design and

continually to redesign the diverse forms of life. Ironically, Gould proves Paley

right: wherever we find design, there must be a designer; wherever one sees contrivance,

one must conceive a contriver. For Gould and for many secular scientists natural

selection functions as a stand in for God.

Could it

be that Darwin, with all his inconsistency and confusion, was closer to the truth

than Gould? Could it be that the most perceptive observers of nature draw their

metaphors and spin their analogies freely from religious tradition as well as

from the laws of mechanics, drawing upon the depths of imagination as well as

technical reason?

In Darwin's age and in reaction

against the stranglehold which the doctrine of special creation had upon the human

imagination, it may have been necessary to construct a secular science, free of

all appeals to God. In the closing moments of the twentieth century, however,

when nature is not generally taken to be a window looking out upon divinity, it

is an opportune moment to recapture something of the grandeur in this view of

life. Nature is at once a sequence of events ascertained by science and an act

of God. It may be time, in other words, to repair the breach that has opened up

between the Darwins and the Paleys, to acknowledge that they were never that far

apart, and to continue searching for a conception of the origin, end, and purpose

of life that invites not only our continuing study but also our praise.

The Galapagos

Islands

1. Neal C. Gillespie. Charles

Darwin and the Problem of Creation (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1979),

p.87. 2. Gertrude Himmelfarb, Darwin and the

Darwinian Revolution (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1959), p.65 3.

Ibid., p.75. 4. Ibid., p.75 5.

Ibid., p. 79. 6. Ibid., p.79. 7.

Ibid., p.80. 8. Charles Darwin, The Autobiography

of Charles Darwin, ed. Nora Barlow (London: Collins, 1958), pp.85-87. 9.

Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species (New York: Collier and Son,

1909), p.500. 10. Charles Darwin, The Descent

of Man; and Selection in Relation to Sex (New York: A. L. Burt, 1874), p.694.

11. William Paley, Natural Theology: or, Evidences

of the Existence and Attributes and of the Deity, Collected

from the Appearances of Nature (Boston: Gould, Kendall and Lincoln,

1849), p.6. 12. Ibid.,p.6. 13.

Ibid., p.13. 14. Ibid., p. 26. 15.

Ibid.,p.26. 16. Ibid., pp. 293-94. 17.

Darwin, The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, p.87. 18.

Gillespie. Charles Darwin and the Problem of Creation, p.83.

19. Ibid., p.133. 20. Ibid.,p.84.

21. Stephen Jay Gould, The Panda's Thumb: More

Reflections in Natural History (New York: Norton, 1982), p.64. 22.

Ibid.,p.66. 23. Darwin, The Origin of Species,

p. 487. 24. Ibid.,p.91. 25.

Ibid., p. 506. 26. Ibid., pp. 88-89. 27.

Ibid., pp. 505-6. 28. Quoted in Gillespie. Charles

Darwin and the Problem of Creation, p.128. 29.

Darwin, The Origin of Species, p. 506. 30.

Gillespie. Charles Darwin and the Problem of Creation, p.87.

31. Ibid.,p.87. 32. Gould,

The Panda's Thumb, pp. 20-21. 33. Ibid., p.26.

34. Ibid., p. 20. 35. 35.

Ibid., p. 139. | |

One

cannot begin to fathom the dilemma of western culture without reflecting upon

One

cannot begin to fathom the dilemma of western culture without reflecting upon